This post was written in conjunction with the Dueling Divas Blogathon hosted by Lara at Backlots.

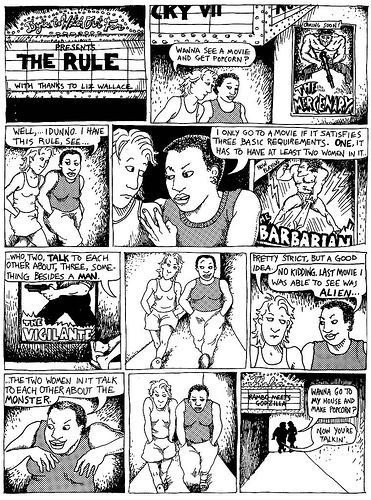

This post was written in conjunction with the Dueling Divas Blogathon hosted by Lara at Backlots.Women in film are often represented as romantic rivals for a male character. Girlfriends and ex-girlfriends, wives and mothers, sisters and fiancées are perpetually warring with each other on the big screen. As the Bechdel test highlights, women are seldom shown as friends, and when they are shown as friends they are still obsessed with love and marriage. We are often exposed to an image of women as bitchy, witchy, and catty. There is no doubt that the media perpetuates this view of womanhood via advertising and news coverage. The current slew of "reality" TV shows is shameless about showcasing the very worst idea of womanhood.

However, there are instances throughout film history when the public has been exposed to alternative, more healthy examples of womanhood. Several of Katharine Hepburn's films include situations where one would expect a "dueling diva" type of scenario, yet in many cases, any semblance of a romantic rivalry is broken down by the ultimate unity, or at least tolerance, of the female characters in question. These examples can be broken down into three distinct categories: communities of professional women, female relatives, and friendships. Hepburn's persona, as a champion of women's equality, serves to bring women together, rather than alienate them from each other. Here are the various ways that the strength of the Hepburn persona as anti-rival is manifested in her films: