"In a 1973 visit to the College, Hepburn told Bryn Mawr undergraduates, "Bryn Mawr isn't plastic, it isn't nylon, it's pure gold... I came here by the skin of my teeth; I got in and by the skin of my teeth I stayed. It was the best thing I ever did. Bryn Mawr was my springboard into adult life. I discovered that you can do anything if you work hard enough. I feel that I was enormously lucky to come here. I am very proud when I see the name, very proud." In 1977, Hepburn was awarded Bryn Mawr's Highest honor, the M. Carey Thomas Award." (Bryn Mawr)

|

| Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn in ADAM'S RIB (1949) |

|

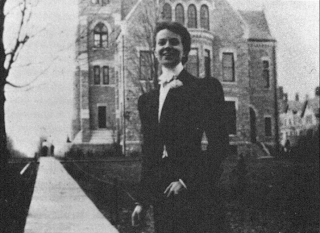

| Katharine Houghton, KH's mother on her first day at Bryn Mawr, c. 1895 |

The fight for equal rights to education, especially higher education, was a fundamental part of the woman’s movement. The history of the women’s colleges runs parallel to the early woman’s movement of the 19th century, rather than to the Progressive Reform movement of Katharine Hepburn's youth. The Seven Sisters colleges were all founded between 1837 and 1889. The significance of these institutions grew as society at large began to embrace higher education as an essential element of success in public life. As the need for social changed evolved, “progressives involved in humanitarian efforts placed high value on knowledge and expertise” (Brinkley 571). There was an increased need for professional and administrative positions as society embraced a rapid growth of a middle class devoted to social change. Because so many of the volunteers involved in the progressive movement were women, they sought education as keenly as any male progressive, leading to the emergence of several women’s colleges, including Bryn Mawr.

|

| Katharine Hepburn in a Bryn Mawr production (Me: Stories of My Life) |

The seven women's colleges on the East coats, known to this day as the “Seven Sisters,” are Mount Holyoke, Vassar, Wellesley, Smith, Radcliffe, Bryn Mawr, and Barnard. Historically, each had its own purpose and reputation and each therefore turned out a specific type of woman. Scholar Helen Bennet describes them thus:

"Seven Colleges – Seven Types: Smith college turns out the doer; Wellesley, the student; Vassar, the adventurer; Bryn Mawr, the social philosopher; Mt. Holyoke, the conservative; University of Chicago, the enterprising; and the state universities, in general, the practical girl." (Dorothy M. Brown 135)As Dorothy Brown explains, “The curriculum at each women’s college tended, as it always had, to reflect the programs of their male Ivy League neighbors.” This meant that for the first time women were being given the opportunity for intellectual equality with men.

M. Carey Thomas was a leader within the feminist movement, and because Bryn Mawr followed the feminist philosophy of its president, Bryn Mawr became a leading feminist institution. Women’s education scholar Helen Horowitz explains, “Bryn Mawr began in imitation. It became the leader. Under M. Carey Thomas, the first feminist to gain control over a women’s college, Bryn Mawr became the innovator in curriculum and campus design."

Bryn Mawr College was founded by Joseph Wright Taylor in his 1877 will. Unfortunately, although Taylor invested much of his time and money into the initial founding of Bryn Mawr, he died in 1880, five years before the first students arrived. It was Taylor's mission to educate young Quaker women for the purpose of their being more able to participate in the Quaker community. He bemoaned the fact that “the advantages of a college education which are so freely offered to men” were plainly being withheld from young women. He made it very clear that the women were not to be educated in a way that would make them better wives and mothers, but rather to make them “capable of stimulating and interesting intellectual companionship,” and “equal to taking part in the thought and discussion of vital things with which Friends were constantly occupied” (Cornelia Meigs 15). The religious nature of the foundation of the college made it permissible for the institution to reject societal standards in order to implement its own.

Above left: the Bryn Mawr cast of "The Truth About the Blayds." Hepburn is second from the right, as a boy.

Bryn Mawr was the first school in America to offer a graduate degree program to women. M. Carey Thomas strongly believed that the graduate school would legitimize the academics of the school, allow professors to stay current in their fields, offer the opportunity for students to participate in original research, and train future generations of women scholars and professors. Bryn Mawr also boasted a student government: “the first in the country at its founding in 1892, was unique in the United States in granting to students the right not only to enforce but to make all of the rules governing their conduct” (Bryn Mawr). Although in some cases President Thomas might disagree with the student government’s rulings, she insisted on principle that they remain autonomous, trusting completely in the responsibility of the students. Later, Katharine Houghton, her sister Edith Houghton, and her daughter Katharine Hepburn would all run into some trouble with the student government.

The curriculum at Bryn Mawr College was set up “to offer women rigorous intellectual training and the chance to do to original research, a European-style program that was then available only at a few elite institutions for men.” Because of its graduate school and its extremely difficult entrance exams, Bryn Mawr under Thomas developed a strong reputation for its academic rigor. Thomas once proclaimed that her “one aim and concentrated purpose shall be and is to show that girls can learn, can reason, can compete with men in the grand fields of literature and science and conjecture” as well as any man (Elaine Kendall 132).

The Bryn Mawr curriculum was equivalent to male colleges, including courses previously denied women, such as psychology, ethics, logic, Christian evidences, Greek and Latin, English lit., German, French, math, history, political science, chemistry, physics, geology, botany, zoology, physiology, hygiene, biology, and art (Meigs 37). Bryn Mawr became known for its Classics because every student was required to have at least a minimal familiarity with both Greek and Latin.

There was also a vigorous academic standard to which all faculty were held, a stern policy that all teaching should be done at that highest possible level, with every department in the hands of specialist, thus limiting the number of branches in order to perfect one at a time. This policy meant that unlike Smith and Radcliffe, which were able to boast a teaching staff made up primarily of women, Bryn Mawr was forced to draw its faculty from male graduates of Johns Hopkins and the German universities. However, Bryn Mawr had established the first graduate program available to women for a purpose – to train women academics as the next generation of scholars and professors. Therefore, although Bryn Mawr was forced to hire a primarily male faculty in order to maintain its high academic standards, the institution was contributing in a big way to the future of women in scholarship.

Although other women’s colleges offered courses in the domestic sciences and social graces, Thomas insisted on strict academics and accused other institutions of becoming “Japanese Geisha schools” (Kendall 179). At Bryn Mawr, a legion of housekeeping staff ensured that no domestic duties ever interfere with scholarship – maids tidied the rooms, made the beds, and cleaned the laundry so that no student would ever be distracted from her studies. This stressed Thomas’ strong views concerning the educated woman and marriage. She knew that girls would automatically tend to put a lot of effort into developing their domestic skills in the belief that they needed to prepare themselves for marriage after college. However, Thomas wished to create an atmosphere of learning at Bryn Mawr, diverging completely from the cottage system at Smith which encouraged students to become homemakers.

Another aspect of feminist life at Bryn Mawr was in the extra-curricular activities. Constance Applebee, the woman who first introduced field hockey to the US from Britain, was a faculty member who led an extensive and intensive athletic program. The students at Bryn Mawr also participated in a number of clubs and social activities. The Graduate Club hosted monthly talks by professors and addresses by prominent speakers. There was also a debating club, chess club, glee club, and an athletic association (Joan Marie Johnson 146).

This campus lifestyle, combining the effects of the graduate school, the student government association, the curriculum, and the social activities, revealed a very important aspect of the feminist nature of Bryn Mawr:

“In a college composed only of women, students did not remain feminine. Through college organizations, they discovered how to wield power and to act collectively; through aggressive sport, to play as a team member and to win; through dramatics, to take male roles.” (Horowitz 163)Although society would have certain expectations of students as young women after they graduated, the Bryn Mawr curriculum and lifestyle set them up in a way that would encourage them to rebel against societal limitation and make their own way as fully capable individuals, prepared to participate fully in professional, political, and social activities.

|

| Katharine Hepburn's graduation photo (1928) |

Very good essay! Bryn Mawr looks like a fantastic place, not only because we don't have to do domestic works as laundry, but because of its whole atmosphere. I was really glad when I first dug in Kate's life and found out that she is a History Major like me.

ReplyDeleteKisses!

What an interesting read. I stumbled on this during my search for colleges in pa. It is so interesting hearing the history that comes with some of these colleges.

ReplyDeletePretty late to mention this but Katharine was not very happy at Bryn Mawr . I actually think that she was depressed at the start of her college life although she did manage to get through it and thrive . In the early 1930s one of the academics was asked about Katharine Hepburn the new movie star and they said they didn't remember her . In spite of this Katharine managed to get through . But my impression is that they failed to recognize and nurture her unique talent

ReplyDelete